Spoiler warning: this post is one long spoiler from start to finish. If you haven’t played Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, and you plan to do so, and you would like to do so without knowing about the legendary plot-twist, reading this post will have a deleterious effect on the realization of that plan. Concerning comments: I'd be incredibly grateful for any corrections and/or refinements you'd care to suggest about this chapter-in-the-making--Google Buzz is my preferred discussion-place now, so comments are turned off here. You’re most welcome to follow me on Buzz, here; you’ll find this post there, too, with any luck, and I hope to discuss it with you there!

KOTOR organizes every player performance around the player’s apparently climactic decision as to how to integrate the knowledge that the player-character (PC) was, before the game began, Darth Revan, the leader of the Sith (advocates and users of the dark side of the Force), into his or her subsequent performance. At that point, when (I estimate) 90% of the game has been completed, with only hints that the PC has a secret in his or her past, the PC learns that he or she was saved, before the game began, by the non-player-character (NPC) Bastila and, when it was found that the PC had no memory of his or her past, was allowed by the Jedi Council to go free in hope that he or she might return to the light side.

I want to take this moment as a kind of locus classicus of the Bioware style, not because other styles of RPG don’t feature similar moments, but because the way KOTOR handles this moment seems to me to share certain key characteristics with the way other Bioware games enable differentiated player-performances. This moment in KOTOR also doesn’t, I’ll try to argue, share those key charactistics with other styles.

Moreover, in the chapter I’m sketching here I want to argue that some at least of those key characteristics are describable in terms of oral formulaic theory. I want to suggest, too, that that description might integrate the Bioware RPG into--here I’ll just be simplistically, though not in my opinion inaccurately, broad--intellectual history more satisfactorily than it has yet been integrated.

To close the loop in a way I won’t be able to in the actual chapter, integrating a theoretically-informed thick description of the Bioware RPG into intellectual history has value in my eyes because it helps me understand my culture better, which in turn helps me shape my practices and performances more effectively to serve the good of all. For example, once I’ve described KOTOR to my satisfaction, I’ll be able to help my students integrate their reading in homeric epic with their performances in KOTOR in a way that advances their ability to analyze culture.

(I don’t know if that’s the kind of thing you wonder about--what the hell an academic thinks he’s doing when he’s writing this stuff that apparently has no value other than filling out his CV--but I always wonder about it. That’s why I think blogging has it all over what’s more usually called “scholarly discourse.”)

Anyway, the key characteristics of the way KOTOR handles this moment that seem to me 1) particular to the Bioware style and 2) describable in terms of oral formulaic theory are the relations of the moment to:

The light/dark slider may be described in several ways. The most usual way to describe it is as a morality scale, by which the player’s choices are given what observers describe, broadly, as moral consequences in relation to the ongoing events of his or her performance. Briefly, a certain (large) number of dialogue choices in the game--for example whether, at this key moment of revelation, to have the PC declare s/he accepts the mantle of dark-side leadership or to have the PC declare that s/he rejects that mantle and will side with the light--, confer light-side points or dark-side points, the totals of which are tracked, in relation to one another, on a sliding scale that is visible to the player at any time.

The light/dark slider may also be described, though, as a ludic system by which KOTOR differentiates player-performances. As the player accumulates a balance on the slider, choices of character configuration--that is, the cost to the PC of certain powerful skills--are shaped by where the PC stands on the slider. For a player on the light side of the slider, skills like “Cure” are less costly, and skills like “Drain Life” are more costly. The player’s dialogue choices are thereby registered at the level of the gameplay so as to differentiate his or her performance from other possible performances at that level, in a way parallel to the differentiation at the level of dialogue, where the player must choose to say certain things and not to say others--choices that trigger the game’s awards of light-side or dark-side points.

At the same time, in a broader context, the light/dark slider differentiates the player’s performance in relation to the range of possible performances as a Jedi in the Star Wars universe, whose dualistic light/dark ethical system is essential to the game, as it is to every part of the discourse of Star Wars. This climactic decision in KOTOR, for example, adds either an enormous number of light-side points or an enormous number of dark-side points to the PC’s total, and thus places him or her decisively in relation to the ongoing performances of the Star Wars universe, whether in games, on film, or in text.

I’ll discuss the way this particular system of differentiation distinguishes the Bioware style from other styles later in this post-series, but my argument will be that in non-Bioware RPG’s that have an analogous scale differentiating player-performances--for example the reputation scale in Bethesda games like The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion--that scale is tied into the events of the player’s performance (or, if you like, the performance’s narrative) quite differently. As we proceed, I’ll be trying to argue that the very different scales to be found in Mass Effect and DragonAge share important elements with the light/dark slider in KOTOR that none of them shares with the reputation scale in Oblivion. To oversimplify just for the moment, Oblivion’s reputation scale isn’t an essential part of the unfolding events of the main quest (partly because the very notion of a main quest is different in the Bethesda style), while the light/dark slider in KOTOR, the renegade/paragon slider in Mass Effect, and the individual approval sliders of party members in DragonAge have a determinative relation to the player’s performance of the central ludic materials of the game.

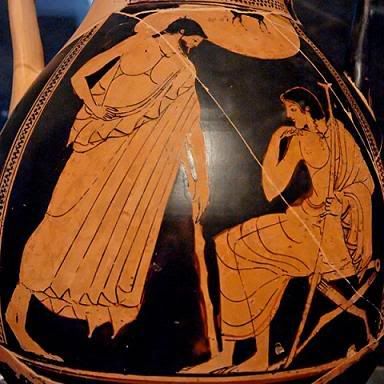

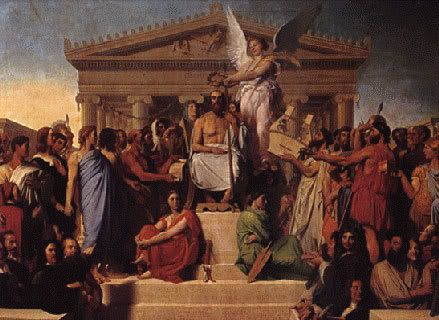

It’s here, I believe, that the concept of composition-by-theme begins to show its worth. To talk about why, I’ll pick two examples from the countless available thematic moments in homeric epic to compare with the climactic “I’m Revan” moment in KOTOR.

When a bard first chose to have Odysseus lie to his father in what we know as Book 24 of the Odyssey, and when a bard first chose to have Patroclus call Hector his third slayer in Book 16 of the Iliad, those choices differentiated those performances from every performance that had gone before, but they did so in relation to the existing epic materials. Those new themes, that is, were already based on old ones (“lying” and “battle-taunting”). In the recompositional process, bards made their choices in developing their themes (remember that in oral formulaic theory a “theme” is a part of a story, like an arming scene or even a whole battle) based on their knowledge of and skill in using the themes that had gone before.

Indeed, when subsequent bards followed them and used those themes (“lying to father,” “victor as third slayer”) in their own performances, they enacted similarly unique performances, in relation to the existing themes, despite the fact that they were using a pre-existing theme. To describe the difference between the Iliad and the Odyssey in a way that goes beyond the obvious and takes into account their geneses in bardic tradition requires that we describe the differing relationships between performance and theme in the two epics. This is the kind of analysis Laura Slatkin does in the essay I mentioned in my last post. That analysis tells us that the bards of the Odyssey re-composed their performances so as to take advantage of their hero’s own relationship to performances like theirs, and demonstrate their virtuosity at such composition.

That sort of argument is well-known to scholars of homeric epic; it has to my knowledge not been attempted on the digital RPG. I want to argue, though, that it should be attempted, because at the moment of decision between Jedi and Sith, the player of KOTOR re-composes his or her performance, even the first time, out of the elements given by the game, and above all in relation to his or her PC’s position on the light/dark slider. This is, I believe, the basic nature of re-composition in the Bioware style: the player at every moment shapes his or her performance with reference to a ludic system that renders the performance meaningful in relation to the entire system of the game, which is at the same time an overdetermined version of the player’s world that productively mystifies him or her about the meaning of his or her choices both in the game and in “real” culture.

From this perpective the homeric equivalent of the Bioware style would perhaps be a sub-genre in which bards sung their heroes’ words and actions according to a very stylized set of requirements (there are certainly examples of poetic genres with not dissimilar stylzations) that rather than the Iliadic focus on glory or the Odyssean focus on wits enforced a focus on a “scale” of diction that related words to themes. Odysseus would for example lie to his father if the bard had earlier called him “Odysseus the crafty,” or not lie to his father if the bard had called him “Odysseus the wise”; Patroclus would be third-killed by Hector if Hector had previously boasted that he was “great in glory.”

I’m beginning to suggest that what makes the Bioware style special is the way it ties the player’s performance explicitly to a fundamental ludic system that itself both represents and determines the register of the game’s range of performances. In KOTOR, that range has to do with the light/dark duality of the Star Wars universe; because of the light/dark slider, performances of KOTOR are always characterized in terms of where they fall on its spectrum--light, dark, or neutral. And because that light/dark duality was from its beginning in the original film Star Wars (now known as Star Wars: A New Hope) a mystifying allegory of real-world ethics, the KOTOR-player’s performance functions to express and perhaps even to shape his or her practices outside the game.

(To be sure, I’ve previously described pessimistic views, on the part of Plato and the designers of Bioshock, about the possibilities for games like KOTOR--that is, games with closed ethical systems--to shape player’s ethical practices. As a believer in the ethical power of homeric epic and the modern RPG, however, I hasten to say that I’m Aristotelian in this regard, though in few others, and I think that such mimesis does effect ethical education.)

In the next sketch I hope to talk about the cutscenes of KOTOR, and in particular the ones that result from the “I’m Revan” moment. The modularity of these cutscenes, and their integrated relation to the player’s re-composition of his or her performance, seem to me highly analogous to a bard’s use of stylized themes like feasts and battles.

KOTOR organizes every player performance around the player’s apparently climactic decision as to how to integrate the knowledge that the player-character (PC) was, before the game began, Darth Revan, the leader of the Sith (advocates and users of the dark side of the Force), into his or her subsequent performance. At that point, when (I estimate) 90% of the game has been completed, with only hints that the PC has a secret in his or her past, the PC learns that he or she was saved, before the game began, by the non-player-character (NPC) Bastila and, when it was found that the PC had no memory of his or her past, was allowed by the Jedi Council to go free in hope that he or she might return to the light side.

I want to take this moment as a kind of locus classicus of the Bioware style, not because other styles of RPG don’t feature similar moments, but because the way KOTOR handles this moment seems to me to share certain key characteristics with the way other Bioware games enable differentiated player-performances. This moment in KOTOR also doesn’t, I’ll try to argue, share those key charactistics with other styles.

Moreover, in the chapter I’m sketching here I want to argue that some at least of those key characteristics are describable in terms of oral formulaic theory. I want to suggest, too, that that description might integrate the Bioware RPG into--here I’ll just be simplistically, though not in my opinion inaccurately, broad--intellectual history more satisfactorily than it has yet been integrated.

To close the loop in a way I won’t be able to in the actual chapter, integrating a theoretically-informed thick description of the Bioware RPG into intellectual history has value in my eyes because it helps me understand my culture better, which in turn helps me shape my practices and performances more effectively to serve the good of all. For example, once I’ve described KOTOR to my satisfaction, I’ll be able to help my students integrate their reading in homeric epic with their performances in KOTOR in a way that advances their ability to analyze culture.

(I don’t know if that’s the kind of thing you wonder about--what the hell an academic thinks he’s doing when he’s writing this stuff that apparently has no value other than filling out his CV--but I always wonder about it. That’s why I think blogging has it all over what’s more usually called “scholarly discourse.”)

Anyway, the key characteristics of the way KOTOR handles this moment that seem to me 1) particular to the Bioware style and 2) describable in terms of oral formulaic theory are the relations of the moment to:

- the light/dark slider;

- the game’s cutscenes;

- the PC’s exploration of relationships with party-member NPC’s, especially Carth and Bastila;

- the final apparent meaning of the player’s performance.

The light/dark slider may be described in several ways. The most usual way to describe it is as a morality scale, by which the player’s choices are given what observers describe, broadly, as moral consequences in relation to the ongoing events of his or her performance. Briefly, a certain (large) number of dialogue choices in the game--for example whether, at this key moment of revelation, to have the PC declare s/he accepts the mantle of dark-side leadership or to have the PC declare that s/he rejects that mantle and will side with the light--, confer light-side points or dark-side points, the totals of which are tracked, in relation to one another, on a sliding scale that is visible to the player at any time.

The light/dark slider may also be described, though, as a ludic system by which KOTOR differentiates player-performances. As the player accumulates a balance on the slider, choices of character configuration--that is, the cost to the PC of certain powerful skills--are shaped by where the PC stands on the slider. For a player on the light side of the slider, skills like “Cure” are less costly, and skills like “Drain Life” are more costly. The player’s dialogue choices are thereby registered at the level of the gameplay so as to differentiate his or her performance from other possible performances at that level, in a way parallel to the differentiation at the level of dialogue, where the player must choose to say certain things and not to say others--choices that trigger the game’s awards of light-side or dark-side points.

At the same time, in a broader context, the light/dark slider differentiates the player’s performance in relation to the range of possible performances as a Jedi in the Star Wars universe, whose dualistic light/dark ethical system is essential to the game, as it is to every part of the discourse of Star Wars. This climactic decision in KOTOR, for example, adds either an enormous number of light-side points or an enormous number of dark-side points to the PC’s total, and thus places him or her decisively in relation to the ongoing performances of the Star Wars universe, whether in games, on film, or in text.

I’ll discuss the way this particular system of differentiation distinguishes the Bioware style from other styles later in this post-series, but my argument will be that in non-Bioware RPG’s that have an analogous scale differentiating player-performances--for example the reputation scale in Bethesda games like The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion--that scale is tied into the events of the player’s performance (or, if you like, the performance’s narrative) quite differently. As we proceed, I’ll be trying to argue that the very different scales to be found in Mass Effect and DragonAge share important elements with the light/dark slider in KOTOR that none of them shares with the reputation scale in Oblivion. To oversimplify just for the moment, Oblivion’s reputation scale isn’t an essential part of the unfolding events of the main quest (partly because the very notion of a main quest is different in the Bethesda style), while the light/dark slider in KOTOR, the renegade/paragon slider in Mass Effect, and the individual approval sliders of party members in DragonAge have a determinative relation to the player’s performance of the central ludic materials of the game.

It’s here, I believe, that the concept of composition-by-theme begins to show its worth. To talk about why, I’ll pick two examples from the countless available thematic moments in homeric epic to compare with the climactic “I’m Revan” moment in KOTOR.

When a bard first chose to have Odysseus lie to his father in what we know as Book 24 of the Odyssey, and when a bard first chose to have Patroclus call Hector his third slayer in Book 16 of the Iliad, those choices differentiated those performances from every performance that had gone before, but they did so in relation to the existing epic materials. Those new themes, that is, were already based on old ones (“lying” and “battle-taunting”). In the recompositional process, bards made their choices in developing their themes (remember that in oral formulaic theory a “theme” is a part of a story, like an arming scene or even a whole battle) based on their knowledge of and skill in using the themes that had gone before.

Indeed, when subsequent bards followed them and used those themes (“lying to father,” “victor as third slayer”) in their own performances, they enacted similarly unique performances, in relation to the existing themes, despite the fact that they were using a pre-existing theme. To describe the difference between the Iliad and the Odyssey in a way that goes beyond the obvious and takes into account their geneses in bardic tradition requires that we describe the differing relationships between performance and theme in the two epics. This is the kind of analysis Laura Slatkin does in the essay I mentioned in my last post. That analysis tells us that the bards of the Odyssey re-composed their performances so as to take advantage of their hero’s own relationship to performances like theirs, and demonstrate their virtuosity at such composition.

That sort of argument is well-known to scholars of homeric epic; it has to my knowledge not been attempted on the digital RPG. I want to argue, though, that it should be attempted, because at the moment of decision between Jedi and Sith, the player of KOTOR re-composes his or her performance, even the first time, out of the elements given by the game, and above all in relation to his or her PC’s position on the light/dark slider. This is, I believe, the basic nature of re-composition in the Bioware style: the player at every moment shapes his or her performance with reference to a ludic system that renders the performance meaningful in relation to the entire system of the game, which is at the same time an overdetermined version of the player’s world that productively mystifies him or her about the meaning of his or her choices both in the game and in “real” culture.

From this perpective the homeric equivalent of the Bioware style would perhaps be a sub-genre in which bards sung their heroes’ words and actions according to a very stylized set of requirements (there are certainly examples of poetic genres with not dissimilar stylzations) that rather than the Iliadic focus on glory or the Odyssean focus on wits enforced a focus on a “scale” of diction that related words to themes. Odysseus would for example lie to his father if the bard had earlier called him “Odysseus the crafty,” or not lie to his father if the bard had called him “Odysseus the wise”; Patroclus would be third-killed by Hector if Hector had previously boasted that he was “great in glory.”

I’m beginning to suggest that what makes the Bioware style special is the way it ties the player’s performance explicitly to a fundamental ludic system that itself both represents and determines the register of the game’s range of performances. In KOTOR, that range has to do with the light/dark duality of the Star Wars universe; because of the light/dark slider, performances of KOTOR are always characterized in terms of where they fall on its spectrum--light, dark, or neutral. And because that light/dark duality was from its beginning in the original film Star Wars (now known as Star Wars: A New Hope) a mystifying allegory of real-world ethics, the KOTOR-player’s performance functions to express and perhaps even to shape his or her practices outside the game.

(To be sure, I’ve previously described pessimistic views, on the part of Plato and the designers of Bioshock, about the possibilities for games like KOTOR--that is, games with closed ethical systems--to shape player’s ethical practices. As a believer in the ethical power of homeric epic and the modern RPG, however, I hasten to say that I’m Aristotelian in this regard, though in few others, and I think that such mimesis does effect ethical education.)

In the next sketch I hope to talk about the cutscenes of KOTOR, and in particular the ones that result from the “I’m Revan” moment. The modularity of these cutscenes, and their integrated relation to the player’s re-composition of his or her performance, seem to me highly analogous to a bard’s use of stylized themes like feasts and battles.