This is a republication of a post from playthepast.org, which in turn was a drastically re-written version of a post that appeared on this blog in its early days.

This is a republication of a post from playthepast.org, which in turn was a drastically re-written version of a post that appeared on this blog in its early days.This post serves as a prelude to some heavy oral formulaic lifting I’m planning to do in a subsequent one, following on from the more general argument I made about immersion in my previous two posts on games and homeric epic. Hopefully, these posts will clarify both the similarities between the interactivity and immersion to be found in oral epic and that to be found in games, and their important differences. My central contention is as usual that the practice of homeric epic was fundamentally ludic, and that an understanding of the rules of that practice, and how they worked themselves out in the narrative of the epics as we have them, can help us understand our own ludic (that is, to use a term that continues to be contentious, gamer) culture better. So even though the play I’m analyzing in this post is mostly far in the past (with a sizable nod towards Bioshock in the end), I’m convinced it has a significant impact on the present and future of playing the past, too.

The first thing you need to know to take this epic journey with me (sorry--the jeux de mots that go with “epic” are really hard to resist) is a little about the ninth book of the Iliad, one of the most famous and influential texts of all Western literature. Let’s start with the inoffensive-seeming word “book” itself: both the Iliad and the Odyssey as we have them are divided into twenty-four separate books. These units of the stories didn’t become formalized into “books” until the epics were written down, probably some time in the 700’s BCE, but there’s reasonably good evidence to suggest that a bard might have sung for an evening’s entertainment just about the same amount of stuff as is in a single book of the epics as we have them. So we can think of Iliad 9 as a self-contained piece of epic performance.

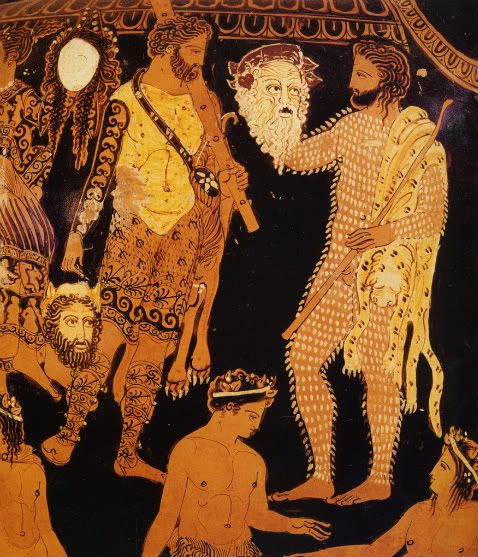

By Book 9 of the Iliad, things have become pretty bad for the Achaeans (the guys usually called “the Greeks”—the ones who have come to Troy to get Helen, the wife of one of their number, back): their greatest warrior, Achilles, the son of a goddess, has refused to fight for several days now, and the Achaeans are losing ground very quickly. Agamemnon, the overlord of the Achaeans and the guy at whom Achilles is pissed off, finally gives in, and authorizes an “embassy”—a delegation, basically—to go to Achilles and offer him fabulous wealth if he returns to battle. In the book as we have it, Agamemnon sends three ambassadors, Ajax, Odysseus, and Phoenix. Achilles, who is (not coincidentally) singing epic to his friend Patroclus when they arrive, responds (long story short) with these immortal lines:

My life is more to me than all the wealth of Troy while it was yet at peace

before the Achaeans went there, or than all the treasure that lies on

the stone floor of Apollo's temple beneath the cliffs of Pytho.

Cattle and sheep are there for the thieving,

and a man can get both tripods and horses if he wants them,

but when his life has once left him it can neither be gotten nor thieved back again.

For my mother Thetis tells me that there are two ways for me to meet my end.

If I stay here and fight, I shall not return alive but I shall have imperishable glory:

but if I go home my glory will die, but it will be long before death shall take me.

To the rest of you, then, I say, 'Go home, for you will not take Troy.'

The simplest reason for this recomposition is that in the absence of writing a bard couldn’t sing a tale the same way he had before--indeed, the system of oral poetics in which he had trained was a way of dealing with the difficulty of accurate memorization in an oral culture. Just as importantly, though, audiences, as we saw in the first book of the Odyssey, always like something new. Bards, as we saw in that passage, made a virtue of necessity, and instead of trying and failing to re-produce a song that had won acclaim, elaborated it differently the next time.

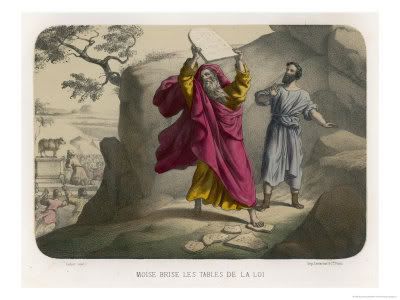

Now a bard who was singing a part of the big story called “The Wrath of Achilles” (what we know as the Iliad) couldn’t change the fact that Achilles comes back to battle, eventually to die. But he could most certainly change the way that coming back went down. At some point, one bard did, and came up with the immortal lines I quoted above about what’s been known forever after as the Choice of Achilles.

But there’s an amazing tension here to which critics rarely call attention, perhaps because it seems to undermine the meaning of the Iliad. The absolute necessity that Achilles will return to battle--the shared knowledge of bard and audience that it must happen--means that the Choice of Achilles actually isn’t a choice at all. And the bard of Iliad 9 uses that necessity with stunning virtuosity. It doesn’t seem to me to be an exaggeration to call this moment in the Iliad the Birth of the Tragic: the choice that is no-choice, in the face of which we must say οἴμοι, τὶ δράσω; (oimoi, ti draso “Alas, what shall I do?”) and know that that question has no meaning.

And strangely enough this is also where we get back to games at last, because games are beginning to use such necessities to similar effects. Achilles, that is, can’t leave Troy any more than the main character of Bioshock can, at the crucial moment of that game, fail to do what the game requires of him, or the player to participate--willingly or unwillingly--in that fictional action.

[Bioshock SPOILERS AHEAD]

At that crucial moment, evil objectivist genius Andrew Ryan tells the player-character to kill him. The murder then takes place in a cutscene in which Ryan says, over and over, “A man chooses; a slave obeys.” The player has no choice, as the Achilles of the Iliad has no choice: both are, according to Ryan’s formula, slaves.

But both the bard of Iliad 9 and the creators of Bioshock call attention to this lack of choice in a way that gives rise to a much richer and more complicated meaning: a kind of meaning that only a ludic narrative practice could yield. The player-character of Bioshock and the Achilles of the Iliad are slaves to the same extent that Andrew Ryan, Agamemnon, the bard, the creators of Bioshock, and we ourselves are all slaves. To understand the non-choice of Achilles and the non-choice of Andrew Ryan is to understand how complex and perhaps illusory is free will itself.

Only an overtly ludic, interactive, immersive performance practice can interrupt interactivity in the service of creating this kind of meaning. The implications, as I hope to show in future posts, are fascinating for our understanding both of Iliad 9 and of Bioshock; in fact, those implications reach even deeper into our intellectual history in the way Iliad 9 underlies both tragedy and a crucial part of the thought of Plato. After all, the guy released from his seat in Plato’s cave has to be dragged kicking and screaming into the light, his interaction with the marvelous shadow-puppet play interrupted for good, in a pale echo of the terrible fate suffered by a gamer who has to take out the trash.