What you’ll see here, if you decide to read this post, and whatever others I manage to produce, is a series of probes in the direction of a methodology of game-criticism based on a fuller appreciation of games’ analogy to oral formulaic epic, and to homeric epic in particular, than I think game-critics have yet deployed. Here’s the abstract I submitted, for starters; I need to state clearly that the final version of the chapter--the one I’m working towards with these sketches--hasn’t been accepted for publication yet, though based on the abstract the book’s editors requested a final version.

Bioware’s epic style: oral formulaic theory and the recompositional process in three Bioware RPGs

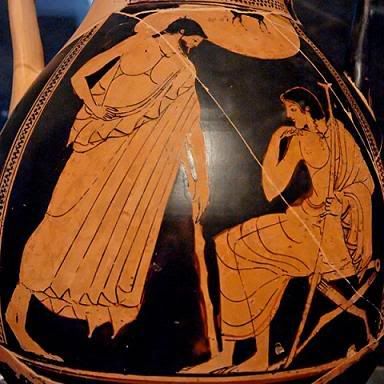

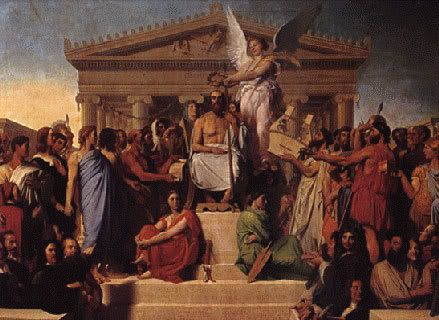

Several writers, beginning with Janet Murray in Hamlet on the Holodeck, have observed the analogy between certain forms of digital game--most notably the RPG--and the oral improvisatory process that gave the world the Iliad, the Odyssey, and countless other works of the Western literary tradition. Briefly, the player of an RPG engages in practices that are highly and interestingly analogous to the practices of the homeric bards, as studied through the comparative materials collected from South Slavic bards and analyzed originally by Milman Parry and Albert Lord. The RPG-player uses the elements given him or her by the game, just as the bards utilized the tradition in which they had been trained; the RPG-player recombines and innovates upon these elements to produce a performance that is irreducibly unique in the occasion as the bard did the same to produce his epic performance. Indeed, as the homeric bard’s performances were later codified eventually to become the fossils we know as the Iliad and the Odyssey, and the singers of tales of other traditions’ into works like Beowulf and The Song of Roland, RPG-players’ performances are these days sometimes codified in video form and shared around games’ communities.

This chapter seeks to contribute to our understanding of the operation and cultural significance of the digital RPG by analyzing key moments in three RPGs by Bioware, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect, and DragonAge: Origins as instances of the same thematic recompositional process delineated by Lord and deployed as a methodology of “composition by theme” by scholars like Laura Slatkin. I demonstrate that a developed “Bioware epic style” may be identified in the way Bioware RPGs use a complex imbrication of dialogue trees, highly modular cutscenes, and party selection choices to allow players the opportunity to compose by theme themselves, creating performances that necessarily stand in relationship to other performances of the same game both by themselves and by others, just as thematic composition in the homeric epics--and in the Odyssey in particular--derives its most important effects from the interactions--indeed the interactivity--of the current performance with the possibility of other, different performances.

I demonstrate that in these three Bioware RPGs players’ choices of character origin, of dialogue, and of party selection, as well as of conduct towards party members, we see the mechanics of the Bioware RPG develop in each game as a way of shaping interactivity with the cultural materials given in the game. I also consider as contrast two other studio RPG styles, the Bethesda style and the Square Enix style, to illuminate the particular operation of the Bioware style. The chapter’s greatest contribution is thus likely to be in the comparisons and contrasts of three different games with one another and with other styles of RPG as outgrowths of a new practice of the oral epic tradition.

So my first notion of what my argument in the chapter will be is very much along the lines of a wonderful--though, I think interestingly flawed--paper by the brilliant classical scholar Laura Slatkin, called “Composition by theme and the metis of the Odyssey” (partly available here on Google books). I’ve taught Slatkin’s essay many times now in various courses on homeric epic, and it never fails to generate productive discussion about the exact extent to which we can say that an oral epic is about something or means something.

Strangely (note my irony), it’s a discussion that’s very highly analogous to discussions I have almost every day on Twitter, Facebook, and Buzz about the possibilities for meaning or “aboutness” in narrative video games. I’ve long ago dispensed, for my own purposes, with the notion that we can talk about games having “authors” in any meaningful sense. But the question of what effect that absence of authorship has on what I prefer to call “meaning-effect” is one with which even homeric scholarship, whose modern incarnation is of course older than video games themselves, and whose roots go back much, much further, continues to have great difficulty in dealing. Game scholarship has made advances in this direction--Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck holds its value very well in this regard--but there is much more to be done, and I’m hoping that my Bioware chapter will help do it.

At any rate, I think formulating this argument will take my own project in a direction it should definitely now go--the nuts-and-bolts critical discussion of what the fundamental comparison on which this blog is founded can actually tell us both about homeric epic and about games, and in particular about story-based video games. Slatkin’s argument is more or less that whoever put the Odyssey together did so 1) with a full understanding of the implications of the multiformity of the oral formulaic themes out of which he was making the thing we now know as the Odyssey, and 2) overtly to place himself (or, if you’d rather, the Odyssey’s narrator) in sympathy, and in friendly rivalry, with his hero Odysseus, in the aspect of metis (cunning). To make a corresponding argument about a game or a set of games would involve actually considering what the narrative materials of RPG’s are, and how they fit together--something that the critic of a novel or a film doesn’t do, something unique to oral epic and games.

My plan is to argue that in three crucial moments of the Bioware RPG’s I mention in the abstract, the player’s performances achieve their meaning-effects in a way describable in the same terms Slatkin uses of the composer of the Odyssey, a way particular to the Bioware style. I want to say that even on the first playthrough--and with increasing complexity as firsthand playthroughs and secondhand knowledge of others’ playthroughs accumulate--the player of a Bioware RPG must make meaning out of his or her performance not only through the performative choices s/he does make but also through those s/he doesn’t, not in the general sense true of all RPG’s but in the specific sense of a confrontation with the games’ potential performances, forced upon the player by the way these specific games deploy their thematic material.

I haven’t decided on the three key moments yet--and of I’ll course support my conclusions about them with many references to other moments in the games--but one of them is likely to be the moment in KOTOR at which the player chooses the way his or her performance will end. (I’m going to put it that way in this sketch because I want to keep it spoiler-free).

Just to end this first sketch with something concrete, I plan to argue that KOTOR configures the player’s performance in such a way that the choice between Light and Dark is a confrontation with the meaningful implications of the player’s performance to that point in the game, and so also with the potential meanings of the performative choices with which the game now confronts the player in the form of specific dialogue-options. As the player’s performance continues from that point, his or her composition by theme--that is, the theme s/he chose to elaborate at that crucial moment--works out its meaning-effects in great part through that performance’s relation to the player’s confrontation with his or her previous choices, above all through the specific valence of the Light/Dark scale that lies at the backbone of the game’s ludics.

Structuring, resolving, and elaborating this kind of choice is exactly what Slatkin’s Odyssey-composer does, with relation to the thematic materials of the Odyssean tradition. The performative choices he made, which echoed centuries of performative choices made by other bards, had the same relation to choices he’d made earlier in the recompositional occasion of his version of the epic: he was forced into the same kind of confrontation. The difference--and the reason I think we can talk about a “Bioware style” as opposed to an “Odyssey style” or a “Bethesda style”--is that the Odyssey-composer’s confrontation was in the register of metis, and involved things like similes, whereas the KOTOR-players’ confrontation is in the register of Light/Dark, and involves things like romantic cutscenes.

If I’m not mistaken about where I’ll go next (though admittedly lately I seem to have less than 50% accuracy on that score), I’ll be getitng more specfic, and more spoiler-y, about that moment in KOTOR. I’m excited about this chapter, and I’d love to discuss it with anyone who’s interested as it develops, in the interest of ensuring that it makes a real contribution to its fields.

I’m going to use the occasion of this post on which I’m eagerly seeking comments to experiment with turning comments off on the blog and requesting that if you're interested in commenting you do so on Google Buzz. If you haven’t experienced how interesting, prolonged, and downright valuable Buzz discussion can be, I recommend giving it a try! You’re most welcome to follow me on Buzz, here; you’ll find this post there, too, with any luck, and I hope to discuss it with you there!