It's not often that I get to play a game in synch with the rest of the gaming world—that is, when the game releases—and most of the time I consider that a good thing, because it means that like a good little scholar I get to absorb the critical context along with the work. I also get to take my time when I play a game late, and avoid the unpleasant realization of just how "bad" I am at games. (Oh, how little consolation it is that I'm "good" at, say, the Iliad.)

But with the start of summer coinciding with the release of Rockstar's Red Dead Redemption, and with my longstanding interest in the relation of the Western to the epic tradition (I teach the Iliad in my myth course with The Searchers as my opening gambit), I thought it might be fun to blog on a semi-regular basis in a sort of diary-commentary form. Here goes.

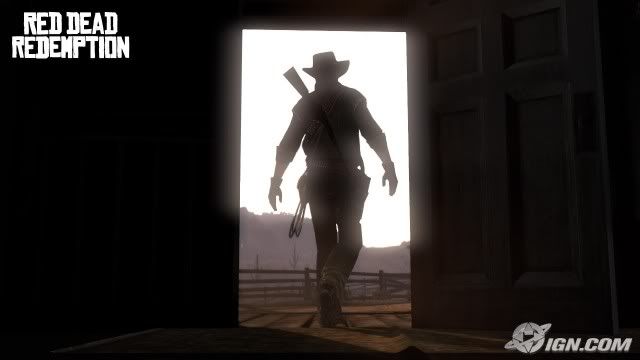

I got to play from 9 to 11 last night, after I got my kids into bed. I entered the practomime as a character whom I later learned is named John Marston. He got off a paddle-boat between two semi-official looking men, who were clearly making sure he went where he was supposed to go. In medias res—or, as my friend Nels puts it, in medium ludum, though I personally think the older phrase is better, because it operates at the level of the res (the matters, the subject) of the practomime.

How did I know I was the man with the scars? Three things spring to mind: 1) he was clearly the man on the cover of the game; 2) he was in the middle of the shot, and in the middle of the semi-official men (I still have no idea who they are [in medias res again]); 3) it's a Rockstar game, and if there's a single disreputable character on screen, it must be you.

I think I'll save my frustration with the horseback-riding and with the narrative itself for another post and explore this practomimetic framing for a moment.

A bard or a member of his audience, when striking up his lyre or listening to a lyre being struck, would have had a subtext already running: this bard sings this kind of song, and thus is likely to be about to sing this kind of song again. Not to mention: when bards sing, this is the range of possible subjects, whether or not this bard decides to sing within his usual domain of styles and subjects.

When the bard began for example μῆνιν ἄειδε. . . (the beginning of the Iliad as we have it), it was like seeing the Rockstar logo. When the bard continued and sang that the tale that night would begin with the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles, it was like seeing a scarred dude get off a paddle boat in the middle of the screen.

In medias res isn't just about the story—it's about the context of the story, and its relation to the tradition. Red Dead Redemption isn't just about John Marston: it's about the player's relation to John Marston, as broadly conceived as that relation can be—inside his or her gaming life, inside gaming culture, inside all of culture.

And that, of course, is where Plato comes in. What will Red Dead Redemption allow its players to learn about the West, and more importantly about themselves? What will those players be, after they have been John Marston? Despite the frustrations I'll bring up as we go, I think even I will emerge transformed by the beautiful and profound aspects of this practomime.