Since I’m just getting back into the swing of things, I’ll start with a couple to which I really have no response other than “Guilty as charged.”

1. The charge of praising unworthy examples of the art of video game, by calling Halo and Bioshock profound.

2. The charge of praising console gaming.

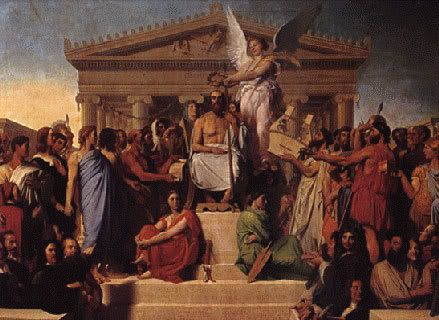

As I’ve said in my preliminary responses, I think a fair reading of my post demonstrates that I’m not claiming that the terrible twosome of Halo and Bioshock are more profound than anything else, including a restaurant menu, if that menu happens to be read in the right context. As several commenters noted, the Iliad (along with a great many classic works which were originally popular entertainment) tends to be mistaken for being something that it’s not, with respect to profundity.

I think the combination of readers’ split-second reactions to the juxtaposition of the word “profundity” and the work Iliad, and the works Halo and Bioshock, may explain how they responded to the post. However that may be, I stand by my basic point, that these games, despite their flaws, including any flaw inherent to their platform, have what I would describe as profound moments. The definition of “profound” is however, finally, very hard to agree upon, and it may be that you’ll in the end simply have to criticize my taste, if not dispute it. (I’m going to handle the matter of how I think that profundity comes about under a different heading.)

The sub-charge of illiteracy, made explicitly by at least one commenter, and a subtext of several others’ remarks, follows nicely here. I would seek to challenge the notion that I have not played a lot of very good games, several of which struck me as more profound, in their ways, than Halo and Bioshock. I cannot claim to have played all the games brought up by commenters, but for every phenomenon inherent to the art of video games that they describe in relation to a game I haven’t played, I have been able to associate a version of the phenomenon in a game I have played; that is, I know what they’re talking about.

But in the the end, characterizing me as illiterate seems to me simply an ad hominem pseudo-argument to justify a failure to engage my claims. If I say something true about video games, why does it matter whether I’ve played Pong? We all know the feeling of having a professor tell us we’re not worthy of talking about work X because we haven’t read work Y or critic Z. Sometimes it’s absolutely true that the point we’re trying to make is vitiated by information we haven’t considered. More frequently, though, the professor is doing that because he doesn’t think it’s worth his time to consider the matter from a new perspective. I try not to do things that way.

Commenters have brought in examples from several different games, in particular Fallout and Shadow of the Colossus, but to my mind these examples, while they lead to fascinating further discussion, aren’t precisely on point with respect to my post, since my post is about a particular aspect of games that connects them to ancient epic, and is not in any way exclusive—that is, I’m not saying that anyone else is wrong about what’s profound because I’m right about it; I think there’s a whole bunch of room for profundity all over the place.

On the other hand, as I continue with the response, I’ll be venturing into territory that wasn’t really covered in my original post, and where I think these examples will be very relevant indeed. There, I’ll come up against the arguments of commenters and in a few cases submit that they’re not looking at the matter in the most helpful possible way. Here are the other responses to my post that I plan to handle in the coming few days.

3. The charge of comparing video games to non-interactive media: here.

4. The matter of choice vs. interactivity: here.

5. The problem of the identity of the artist: player or developer?: here.

Thanks again for this great discussion.