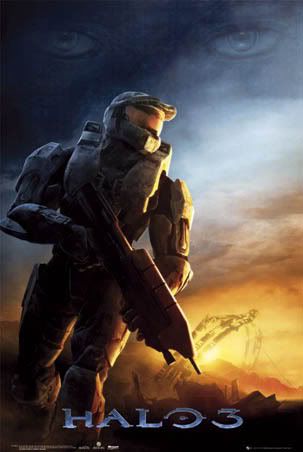

In this post, I’m going to show that the way Halo begins gives us a really good, and really interesting, insight into the similarity between adventure videogames and ancient epic.

Obviously, I would be happiest if I could tell you to go and turn on your XBox and play the segment of the game Halo that I’m going to be talking about in this post; if you do happen to have an XBox, and Halo, and can get to them on such short notice, I highly recommend doing so.

But I don’t think it poses too much of a problem for me to describe the game here, and it will actually serve the important purpose of removing the game, and videogames in general, from the “frame” of the console-and-TV setup in which we’re used to seeing them. I mean “seeing” both literally (that is, sitting on your couch watching your in-game avatar as you play the game) and figuratively (that is, considering and pondering and analyzing).

(Remember that by “adventure videogame” I’m referring to any game in which the player has an adventure through a character whom he or she controls. As we’ve seen, the course of that adventure is partly determined by the designer of the game, and partly determined by the player him or herself.)

Halo begins with some movie-style atmospheric music, and a very, very long shot of a spaceship, next to a mysterious, enormous ring-in-space (the Halo, obviously). We see a series of animated shots, featuring a spaceship captain and an aritificial intelligence that controls the ship, which look like a badly-made computer cartoon (because they’re created using the game’s “engine,” the program used to put all the action in the game on your screen); in the story told in these shots, we get a bit of exposition about what’s going on.

This animation is called a “cut-scene,” a part of videogame storytelling that’s of the utmost importance to understanding how videogames relate to other kinds of narrative art. I’ll be returning to the cut-scene in a future post, but for now I need to call attention to the transition that’s going to be made at the end of it—from the player not having control of a character to the player participating through his or her character.

At any rate, in the cut-scene with which Halo begins, we learn that the ship, the Pillar of Autumn, has been attempting to escape from an alien battlefleet, and has by chance ended up near the Halo. But the aliens, called the “Covenant,” are already there, waiting for them.

Captain Keyes orders the ship to prepare for battle once again, and we see the marines, led by battle-hardened Sergeant Johnson, getting ready “to see Covenant up close.”

We see some technicians receive an order to “open the hushed casket.”

Then, suddenly, we are inside what must be the hushed casket, looking out through a window. The cover opens, and we see one of the technicians standing there. He greets us as the Master Chief, and the game tells us, via the HUD (heads-up display, which simulates the inside of the Master Chief’s helmet), to press X to exit the casket.

When we do, we return for a moment to third-person view, and watch ourselves, a magnificent, armored warrior, whose face is obscured entirely by a shining visor, step out of the cryogenic chamber.

Quickly, we return to the action, and, if this is the first time we have played, are instructed in a series of “diagnostics” that acquaint us with the controls—the game’s tutorial. At the end of the tutorial, aliens suddenly blow the door open, and we are told to get to the bridge to see Captain Keyes, as we watch our first friends, the techs, slaughtered by the aliens.

We are weaponless, as yet, so we must dart through hordes of aliens who are trying to kill us, learning a few things, like how to crouch and how to use our flashlight, on the way. It is easy to get lost in the maze-like corridors of the Pillar of Autumn, and so the arrows on the floor pointing to the bridge come in handy. Even so, we need the help that comes to us in the form of a marine who tells us to follow him to the bridge, and finally leaves us at the entrance.

When, finally, we stand before Captain Keyes, the view changes back to third person for another cut-scene, and we receive an update on the situation. At last, having received as a companion the famous Cortana, an Artificial Intelligence who also serves as a a guide and a narrator, the Captain hands us his revolver and instructs us to find our way to the lifeboats. The game now begins in earnest, and as we exit the bridge we must start shooting the aliens who are trying to shoot us, or to blow us up with their glowing plasma grenades.

Let me note that this game is violent, but let me also re-launch the comparison that constitutes the main theme of this blog by noting that Halo is nowhere near as violent as the Iliad or the Odyssey.

In considering my description of the action at the start of Halo, you’ll notice first of all that we are put smack into the middle of a story. They had a name for that storytelling technique in the ancient world: they called it a beginning in medias res: “into the middle of matters.” Beginning in medias res has been considered one of the hallmarks of epic since Chryses walked into the camp of the Achaeans at the start of the Iliad, and so I want to begin this comparison of adventure video games with ancient epic literally at the very beginning, and talk about beginnings themselves.

Next time: in medias res, not in mediis rebus (it takes a classicist, after all!)