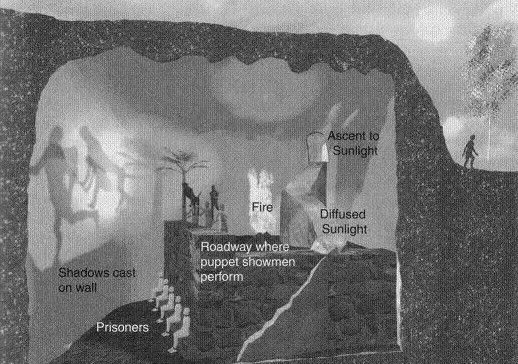

The last post was an attempt to outline the scope of this series of posts about Plato’s cave and video games. In this post, I want to make the connection between the homeric material I’ve been discussing through most of the Main Quest and the cultural move that Plato makes in the myth of the cave, the one I started talking about in the last post—a move that’s usually overlooked. Briefly, Plato makes a special and peculiar effort to make the cave’s shadow-puppet play interactive.

Socrates: I said, “ . . . if they [that is, the prisoners of the cave] were in the habit of conferring honours among themselves on those who were quickest to observe the passing shadows and to remark which of them went before, and which followed after, and which were together; and who were therefore best able to draw conclusions as to the future, do you think that [the man who had seen the real world outside the cave] would care for such honours and glories, or envy the possessors of them? . . .What does Plato mean when he has the prisoners of the cave interacting with the shadows they see in that rudimentary game of observation, remark, prediction, and measurement?

“And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady (and the time which would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be very considerable) would he not be ridiculous? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one tried to loose another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.”

It’s important to remember that when Plato introduces the idea of the shadow-puppet play itself (the play, that is, that's all the prisoners know of the entire world), he’s drawing on well-known cultural material. Socrates’ interlocutors know what a shadow-puppet play is, and Plato’s readers know what a shadow-puppet play is.

But when Plato says that the prisoners have competitions in observing, remarking, predicting, and measuring, he’s making stuff up, the way someone in the modern world would be if he said, “Imagine a movie theater, where everybody is tied down and can only see the movie. Now imagine that the people in the theater have contests in figuring out what’s going to happen next in the movies.” Movie theaters we know. Contests for predicting plot twists we don’t know, but can readily conceptualize.

So what does Plato mean? He means culture, obviously: the things that people do every day, in particular of course the things they do in Plato’s Athens, are for Plato like contests about a shadow-puppet play. Our lives, our never-ending quests for success and prosperity for ourselves and our families, are like a game in which we’re trying to get rewards for our interactions with the stuff we find in the world.

Life, Plato is saying, is like a video game.

Ken Wark has recently done some pretty interesting work along precisely these lines. His book Gamer Theory can be read as a meditation on the theme of interaction introduced into the myth of the cave by Plato.

My own mission in this post-series, though, is to use Plato’s insight not to talk about culture in general but to talk about games themselves.

But (you might object) isn’t that reading the myth of the cave incorrectly? Plato didn’t want to say anything specifically about video games (or shadow-puppet-plays, or imaginary contests at shadow-puppet plays), did he?

Actually, he did. Because the shadow-puppet play is very clearly an instance of mimesis, the cultural practice Socrates and his interlocutors have already spent a lot of time talking about, in the context of their discussion of education. Socrates demonstrates to his interlocutors satisfaction, if not to ours, that epic—that is homeric epic—Iliad and Odyssey—and especially tragedy and comedy make use of mimesis. The word is usually translated “imitation,” but in order to grasp what’s really going on in the cave we need to translate it as “performance as somebody else” or “identificative performance.” Mimesis is, more or less, playing pretend.

That discussion, again, was about education, and another overlooked part of the cave is the way Socrates introduces it. When we understand that introduction, however, we understand much more about what’s really going on in the cave, and how it relates to the rest of Republic. I’m going to give it to you in Greek, first, because there’s a word in there that doesn’t have a good single translation:

meta de tauta, eipon, apeikason toioutoi pathei ten hemeteran phusin paideias te peri kai apaideusias.The cave is about education, and because Plato’s problem with education is mimesis and the shadow-puppet play is mimesis, the cave-culture-game is in fact not just about culture in general, but also about the mimesis’ that go to make up culture: Homer, tragedy, video games. It’s very much worth noting by the way that I’ve already spent a lot of time on this blog making it clear that homeric epic was essentially interactive, and that tragedy too was highly interactive in the way the city participated in putting on the productions and in judging them, and that there were highly prestigious competitions in both homeric epic and tragedy, for which the city awarded major prizes. The analogy with the cave-culture-game, that is, is quite exact.

“After this,” I [Socrates] said, “liken to the following sort of state our nature concerning both education/culture [paideia] and non-education/non-culture [apaideusia].”

That’s enough Plato for one post, I think, but it’s really only half the set-up, because although Plato puts down the controller of epic and tragedy, he picks up the philosophy-controller at the same time.

It’s very interesting, though, to turn at this point and look at a game like Bethesda's The Elder Scrolls IV Oblivion, where a an ethical scale of “fame” versus “infamy” partly determines the course of the story. A microcosmic way to look at this side of Oblivion and games like it is to consider the example of the Dark Brotherhood storyline, which only opens to the player-character when he or she has committed a murder—something the player-character is not obliged by the game to do.

On the face of it, such an efficacious choice—that is, the choice to commit murder has a decisive effect on the narrative—seems to make Oblivion different from the cave-culture-game, which consists only of observation, remark, prediction, and measurement of shadows. The choice to commit murder would seem to be a mimesis of a real ethical decision, capable of making the player think about things that matter from an ethical point of view.

Aristotle would almost certainly agree that the choice to commit murder in Oblivion is capable of that. Viewed inside Plato’s cave, however, the choice looks much less efficacious than it might at first seem. Getting to do the Dark Brotherhood storyline is a reward like other rewards in the game—the choice is measured in terms of the reward within the game, and not in terms of whatever real rewards there might be for making real ethical choices.

Plato’s point is not just that Oblivion and homeric epic are only games (or epics) and thus have no effect on the “real world,” but more importantly that games and epics deceive their players into thinking that they and their choices matter in the “real world,” when in fact those things only matter within their closed systems. As film studies recognized in the 1970’s, the cave, like the cinema, is an apparatus along the lines of what Louis Althusser called the ideological state apparatus, among whose functions is to catch people in culture.

Like Oblivion, like homeric epic, the cave-culture-game is a mimesis that immerses its players so deeply that they’re committed to believing it real. As I proceed in this post-series, I’ll seek to show that Plato wasn’t out-to-lunch in seeing a danger there, but that he and Aristotle each give good reason to hope to avoid that danger and create constructive art in the process, and that game-designers and gamers alike, often unwittingly, are realizing those hopes.