I think it’s now probably time to tackle Bioshock. My chapter on ethical education in the cave and in games, featuring the same reading of Bioshock I’m doing here, looks set to appear in the Fall, in what’s going to be a very exciting IGDA volume on ethics and game design. I think, with that academic version completely under my belt and in my rear-view mirror, I can without my eyes crossing too severely work up a version that’s more fun.

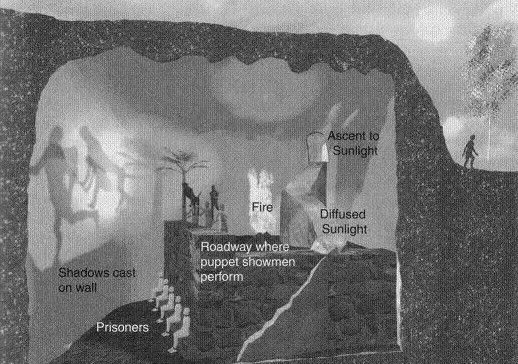

Here’s the claim I’m going to make: the much-discussed ludonarrative dissonance that constitutes Bioshock’s ethical system does not rob the game of ethical meaning, but rather enacts a decisive and meaningful disruption in the player’s performance of the cave-culture-game. That disruption, I claim, has the power to bring about in the player of Bioshock the same sort of ethical reflection enabled by Republic.

There’s a context for this argument that I’m going to spread over several posts; the context has to do with how Bioshock is different from games like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (KOTOR) and Oblivion and GTAIV. It seems, though, to make sense to lay out the big claim first, and thus give the elements of the whole argument-cum-context some breathing space and some time for others to comment. Right now, I want to put forward the central pillar of my argument.

Please be advised that this argument is necessarily chock-full of spoilers of the worst sort.

The central pillar: the harvest/rescue dynamic of the game must be understood in association with the interruptions of interactivity that arise in what I call, as shorthand, the death-disarm sequence. Only when we understand them together can we grasp the critique of objectivism (and the various versions of it that undergird important parts of our culture) enacted by Bioshock.

The harvest/rescue dynamic is the usual focus for critique of the ludonarrative dissonance of the game. The central characteristic of the dynamic, as Clint Hocking pointed out, is the equality of effect on gameplay of doing the “bad” thing (“harvesting”—i.e. killing the Little Sisters) and of doing the “good” thing (rescuing them). Hocking argued that this equality of effect renders the ethical system of the game meaningless, and that it creates a dissonance between game and story that he found blameworthy.

The death-disarm sequence has attracted some critical attention as well, most cogently I think from Iroquois Pliskin, but perhaps not as much or as contentious as harvest/rescue. By the shorthand “death-disarm” I mean to refer to the entire sequence of the cutscene in which your character kills Andrew Ryan and the gameplay sequence that follows, in which the game will not progress unless you obey Atlas and disarm Ryan’s auto-destruct sequence.

At that point in the game—the disarm part of death-disarm—from the standpoint of the your world (your culture, really), you certainly have a choice of actions. You can do any number—an infinite number, really—of different things in the narrow space of Andrew Ryan’s office, like running around, jumping, and shooting at targets. You can also cease playing the game at that point, and turn off your PC or console. From the standpoint of the mimesis of Bioshock (see this post for more on mimesis), however, you have only one choice: to disarm the self-destruct sequence, thus verifying and enacting Atlas’ control over you.

In death-disarm, that is, Bioshock enacts a failed disruption of its closed ethical framework, which is exactly analogous to the failed disruption of the released prisoner in the cave.

For the thinking player of Bioshock, the crushing ethical blows of frustration in being unable not to kill Andrew Ryan, and then of being unable not to disarm the self-destruct, serve to expose the ethical system of the game—and thus of all games—as being like Andrew Ryan’s objectivist dystopia: instead of a world where every man can be a king, Ryan created a world where that very notion made every man a slave. As he is accepting death at the player-character’s hands, Ryan repeats over and over “A man chooses; a slave obeys.” He, and Bioshock, however, demonstrate just as Plato’s cave-culture-game demonstrates, that the dangerous illusion of choice presents the true ethical problem.

Here the harvest/rescue “choice” comes into its own. Precisely in that it is not a choice at all, in terms of the actual gameplay of Bioshock, it enacts through its ludonarrative dissonance itself the dangerous futility of choice. Choice, that is, is exactly analogous to the cave-culture-game, and to the ethical system of games like KOTOR. We must somehow find a way to make ethical choices that does not presume that those choices are freely made, that understands how determined by culture our “free” choices are.

How can we do that? The lesson of the cave-culture-game and the lesson of Bioshock are the same, paradoxical, frustrating precept: you can’t do it in the game you’ve got—it would break the game to try; find a new game. Republic has the benefit of containing the cave-culture-game within its over-arching, brilliant performance of Republic. The reader of Republic can take some comfort in knowing that the dialogue he or she is reading is at least Plato’s best attempt at the new game with the better ethics. But Plato’s need to return to the ideal city in Laws, a work written at the end of his life, indicates very strongly that the perpetually dissatisfying lesson that realizing a better ethical framework requires breaking the old one is as much a part of Republic as it is of Bioshock.