I had the incredible privilege last week to serve as the designated classicist—perhaps even the designated humanist—at the Games+Learning+Society conference in Madison, Wisconsin. (It's an unofficial, self-appointed position.) My presence there, in the strange and wonderful space where the games industry and the burgeoning field of educational technology meet, would never have occurred without the close and immensely fruitful collegial relationship I've had over the past two years with Michael Young, who doesn't (I believe) get enough attention as a pioneer in his field of educational psychology and its relation to educational technology.

Others have reported broadly and emphatically about the sweep of the conference, from Kurt Squire's call to look at games as possibility spaces (my own take would be that we should start speaking of games as one kind of possibility space—or, better, practomime—in which learners gain the power to transform themselves) to David Wiley's call to realize the gains that only true openness of information can bring (my own take would be that, well, yeah—but with narrative, please). (Worth noting that Wiley is yet another teacher who independently started grading in XP; there must be something in the air—and the murmur that went through the room of what I'd call shocked approval at that slide indicates that that air's scent has been wafting over the lakes of Wisconsin.)

So my contribution to the post-conference conversation is to say "More humanities, please!"

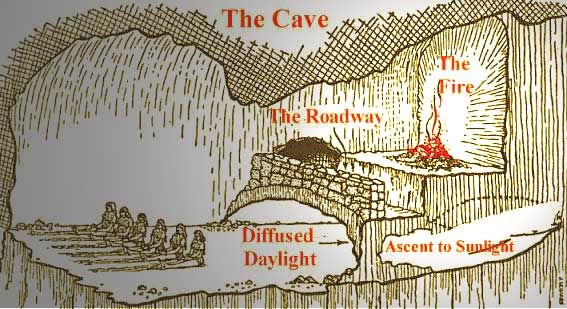

I think there's enormous potential both for the new game/ed-tech inter-field (if you will) and for the ancient inter-field of the humanities in broadening their points of contact: ed-tech could gain a connection to the deep roots of culture; the humanities could gain the kind of traction over the modern world for which their practitioners have been longing. The new "field" of digital humanities (scare-quotes because it's widely agreed not to be a field but rather a set of methodologies) is questing towards some way of making the humanities relevant to the digital age; for a couple years now I've had the niggling feeling that there's something off about that quest—simply put, the humanities are relevant to the digital age, whether they're carried out digitally or in analog form. If Facebook is an instantiation of Plato's Cave, the way we describe it thus—that is, whether we prove it by data-mining or verbal argument in Latin on parchment—has no effect on the validity of the point, though of course it may well have an effect on how large an audience the argument reaches and persuades.

I don't mean to suggest that digital methods are not quite possibly the best methods available for humanities research—simply that we shouldn't look to them to assert the relevance of the humanities to those whom we'd like to keep us in business. Rather, I think what I saw at GLS last week can help us make a much stronger claim to relevance—a relevance that goes well beyond our tools, and into the very constitution of human culture—and even the survival and increase of culture's constructive elements (whatever we should declare those elements to be, a point on which reasonable people are always bound to differ despite general agreement that there are such constructive elements, and that they should survive and increase).

Helped by the absence of any formal educational institutions (as we conceive of them) to think past, Plato was able to see that learning and culture—and thus learning and the humanities, though of course the humanities were at that time many, many years from existing in the semi-formal sense in which we know them—are locked in a dance so intricate that it could be expressed metaphorically as the chains that hold the willing audience in their places in the Cave. As I've demonstrated elsewhere, Plato allegorizes cultural learning as something we can recognize under the current use of the word "game"—or, to put it purely functionally, under the prevailing use of that word by the GLS Conference's attendees.

Because we on the other hand do have formal educational institutions to think past, much of the energy at GLS is understandably taken up with figuring out how to think past them. How do we get administrators to let us bring games into the classroom? Above all, what's the evidence for the benefit of games in schools, and how do we use it, and then get more evidence? These questions are urgent ones, but I'd like to suggest another one, based on humanistic inquiry: if culture is itself, as Plato saw, a sort of game (or a practomime, or a possibility space), and thus school is already a game, how can we redesign this game, this cave, so that all the learners in the schools, in the universities, in the cities and towns and villages, gain the culture-skills they need to make the game a better one for all humanity?

That's the kind of thing I think humanists are best equipped to wonder about—and, I like to flatter myself, maybe classically-trained ones best of all. I'm pretty sure I'm going to spend the summer and the fall pondering precisely that question, since I'm putting together two practomimetic courses based on Plato's understanding (and perhaps misunderstanding) of Athenian culture and culture in general, and since I'm also working with my socii to develop a new practomimetic Latin curriculum for both high school and college classes. Expect more in this vein, as well as about Red Dead Redemption and (I fervently hope) Mass Effect 2 and DragonAge!