Why do the in medias res thing I was talking about last time, though—besides that it’s a fun way to tell a story, and perhaps even that it “grabs” you? There’s actually a much more important reason for the beginning in medias res, and there’s a word for it that’s so important in gaming culture right now that it’s more or less a buzzword, and even a bit of a cliché by now: the word is immersion, and it would be fair to say that immersion is the phenomenon of gaming culture that I believe holds the key to understanding what games do, and what they can do.

Let’s approach it first from the broadest perspective. As in the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Aeneid, so also in Halo: the audience is thrown into the narrative, and left to follow the story’s clues about what part of the story they have come into, and what's going on. The effect is to make the participant more truly part of the story, whether the participant is holding a controller or a lyre, or just listening to a bard sing a story they feel like they already know, or watching a friend play Halo, because they’ve been put into the midst of it.

That was the way with ancient epic, and indeed I would suggest that Halo accomplishes this insertion of its audience even more effectively than ancient epic could, by waking you from sleep.

In Halo, too, what we might call the “moment of immersion,” when the story sucks the audience into itself, stands out very clearly, because at that moment, suddenly, the player’s controller actually controls the character. When we observe that the story-telling isn’t entirely in the first-person—that the cut-scenes have an essential role in telling the player what’s happening, and in giving meaning to the player’s actions as the character—it seems at first that the moment of immersion moves the player from what we might call “regular old storytelling” into the completely new, completely immersive form of storytelling of the adventure video-game.

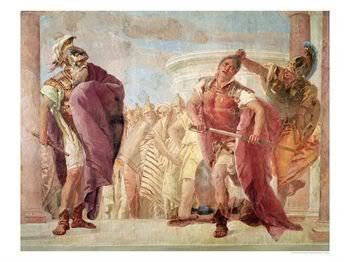

But the point of this blog is to say that that moment of immersion is actually the same as the moment when the bard of the Iliad says “From the time when the two stood quarrelling, the son of Atreus, lord of men, and godlike Achilles.” At least that’s one way to put my big idea. Just to hang it out there, I’ll also put here in a single sentence the reason I think that claim is true: at both moments, the one in the Iliad and the one in Halo, the participants in the occasion, whether of gaming or of epic, take part in the creation of their own version of a story that for that very reason comes to be about them.

I think it’s fairly easy to see how the story of an adventure video game comes to be about the person playing the game—especially when we think of the sort of game called an RPG (role-playing game), in which a player creates a character over whose make-up he or she has a great deal of control (in that he or she chooses the character’s class and abilities and these days can even customize the character’s appearance to a very great degree). The moment of immersion is perhaps simply a very striking line of demarcation between a story about someone else and a story about the story’s actual real-time participants, in the telling of which those participants have, yes, a role to play.

It’s less obvious, of course, that the storytelling of the Iliad and the other ancient epics have something like that moment of immersion, and so to make this comparison clearer it’s necessary to go into some detail about the strange way those epics came together, and what that meant for the later epics that came along, and were created in a way that’s more familiar to us (that is, a writer like Virgil writing down the Aeneid on the Roman equivalent of paper).

Next time: the interactivity of the Homerids (yes, for reals). Also, what the heck a Homerid is.